In 13 communities across the United States, the only thing remaining of the nuclear reactors that reliably pumped out millions of megawatt-hours of electricity over their lifetimes is the securely stored used fuel tucked away in massive steel and concrete dry cask storage modules. This “stranded fuel” (as the Department of Energy calls it) is first in line for ultimate storage in a federal repository. Unfortunately, the Yucca Mountain federal repository project in Nevada has been delayed long past its original 1998 opening date.

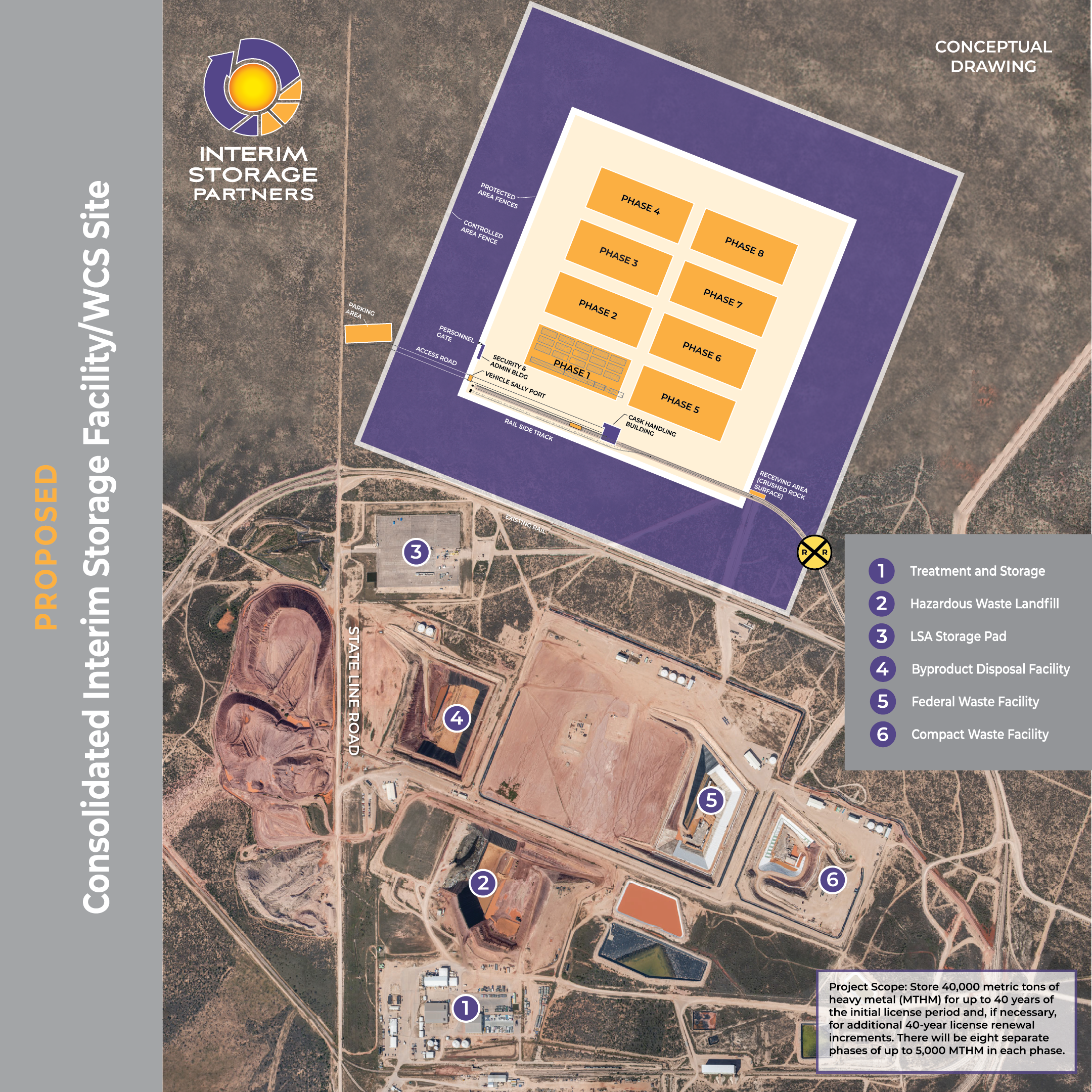

Interim Storage Partners, being formed by Orano USA and WCS, has a solution. ISP is pursuing a license to construct a consolidated interim storage facility (CISF) for used nuclear fuel at the existing WCS disposal site in Andrews County, Texas. The joint venture will request that the Nuclear Regulatory Commission resume its review of the suspended CISF license application originally submitted by WCS in April 2016 and docketed by the NRC for review in January 2017 (Docket No. 72-1050).

The ISP joint venture combines the strengths of Orano’s decades of expertise in used nuclear fuel packaging, storage and transportation with WCS’ experience operating a unique facility serving both the commercial nuclear industry and the U.S. Department of Energy. ISP proposes an initial 40-year license to consolidate and store an eventual total of 40,000 metric ton of used nuclear fuel, developed over eight flexible phases. The development of the WCS site has long been recognized and supported in West Texas as an engine for regional economic development. Andrews County has passed a resolution of support for the CISF initiative.

With an interim storage option, the United States could finally begin the process of removing stranded used nuclear fuel from local communities and consolidating it at a single secure site while an ultimate long-term federal facility is debated.

For storing the used nuclear fuel, the CISF design includes robust above-ground modules constructed of thick reinforced concrete, and offering superior high-shielding properties. These storage modules are proven to withstand environmental and external hazards including tornados, earthquakes and flooding. The internal corrosion-resistant stainless steel storage canisters incorporate advanced materials and support structures that efficiently conduct and remove the residual used fuel heat.

The above-ground structures enable easy loading and access for inspections, monitoring and maintenance during canister safety programs. The design life of the proposed WCS CISF storage system is 100+ years.

- Eliminates multiple ISFSIs (Independent Spent Fuel Storage Installations) in communities nationwide

- Complements a national repository

- Communities can repurpose or resume economic development of shutdown sites

- Economic benefits to hosting CISF community

- Transportation assets can be re-used for transport to final repository

- Development of repackaging facility

- Investment in safety, security and maintenance

- Eliminates management costs and support functions for multiple ISFSIs

Highlights of ISP CISF License Application

General

- Phase 1 of the Interim Storage Partners (ISP) Consolidated Interim Storage Facility (CISF) project will require approximately 155 acres, plus 12 acres for administrative and parking facilities.

– The entire site through Phase 8 will require approximately 332 acres or less than 2.5% of the WCS site-wide acreage.

- By 2053 (approximately 31 years after the ISP CISF estimated opening) there will be 71 shutdown reactor sites in the U.S

Federal Liability for Lack of a National Repository

- A recent Department of Energy (DOE) estimate of the federal government’s liability for storage costs is $24.7 billion if a pilot CISF opens in 2021 and a full CISF opens in 2025.

- Expenditures paid through 2016 have been $6.1 billion.

- The industry estimates that the government’s storage liability for all utilities with which DOE has contracts ultimately will be $50 billion.

- Nuclear Waste Fund’s 2016 Financial Audit Statement noted the net value of the fund was $38.8 billion.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

- Cost-benefit analysis focused on cost of “Proposed Action” vs. “No Action Alternative” of storing 40,000 MTHM from shutdown/decommissioned reactors for 40 years.

- Total benefits of proposed action = ~$6.7 billion.

- Total cost of proposed action = ~$5.2 billion.

- Benefits exceed costs by ~$1.5 billion using conservative financial assumptions.

DOE Reference in Application

- The Department of Energy (DOE) has a legal obligation to remove used nuclear fuel from the original reactor sites where it was generated. Utilities litigate against the DOE to recover damages resulting from DOE’s failure to meet contractual obligations and begin removal. The DOE’s liabilities due to ongoing partial breach of contract are estimated to total $27.1 billion if the DOE cannot take custody of the material by 2021.

- ISP’s license application specifies that the title holders of the used nuclear fuel at the commercial nuclear reactor sites be responsible for its transport to the CISF.

- ISP proposed a license condition in its application that obligates ISP to enter into an agreement that would ensure the interim storage of used nuclear fuel is properly funded by DOE.

- License condition stipulates that the contracts must be in place prior to commencement of operations at the CISF.

Ownership and Liability Issues Associated with Consolidated Interim Storage of Used Nuclear Fuel

Executive Summary

When the federal government failed to meet its obligation to take title to used nuclear fuel by 1998, it created a liability that has cost American taxpayers $6.1 billion through 2016 as a result of lawsuits filed against the government for its failure to meet that deadline.

By its own estimates, the government indicates that its liability will total almost $13 billion by 2020 and could total as much as $30.1 billion. They estimate that amount will increase by approximately $500 million per year if the government does not find a way to begin satisfying its obligations by 2022. One of the primary benefits of HR 474 by Congressman Conaway (R-TX) and Congressman Issa (R-CA) is that it finally addresses this long-standing problem. This legislation offers the federal government the opportunity to begin meeting its contractual obligation to utilities and their ratepayers and it would relieve taxpayers of the burden of paying those stakeholders damages for the government’s failure to begin taking title to used nuclear fuel in 1998, as specified by law.

Ultimately, this legislation could save the taxpayers, at a minimum, $500 million a year. These damages are paid out of the U.S. Treasury’s Judgement Fund – not through an appropriations process or from utility ratepayers.

For consolidated interim storage of used nuclear fuel to become a reality, the key ingredient is no different than for permanent disposal: The federal government must take title to the waste and assume future liability.

The Price-Anderson Act

In the 1950s, the nuclear energy industry’s financial security was threatened because no private company would underwrite liability insurance for nuclear power plants. In the interest of developing this emerging industry, Congress established a way for the industry to have a no-fault-type insurance mechanism where utilities pay into a fund with a ceiling (which has been amended several times) and receive partial indemnity.

Congress enacted the Price-Anderson Act in 1957 to create a pool of funds to provide compensation to the public for incurred damages in the event of a nuclear incident – no matter who was liable.

In addition to the power plants, the Act also covers DOE facilities, private Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) licensees, and their subcontractors including uranium enrichment plants, national laboratories and the Yucca Mountain facility.

Congress has amended the Price-Anderson Act several times and continues to be an effective mechanism to support the nuclear industry.

Any Consolidated Interim Storage Facility (CISF) would be a licensee of the NRC and a contractor of the DOE, with regulatory requirements imposed on all aspects of the operation, including security and liability. Oversight would include periodic inspections and audits conducted by regional inspectors within license conditions. All of this occurs at operating interim storage facilities across the country today.

Furthermore, according to the DOE’s report to Congress on the Price-Anderson Act, “…The report reviews DOE’s experience under the 1988 Price-Anderson Act Amendments that grant DOE authority to impose civil penalties for violations of nuclear safety requirements by indemnified contractors, subcontractors and suppliers. This authority has proven to be a valuable tool for increasing the emphasis on nuclear safety and enhancing the accountability of DOE contractors.”

Indemnification of DOE contractors under Price-Anderson would not affect the standard of care required of a CISF regarding its used nuclear fuel operations.

In assuming liability for this waste, DOE will require the waste to be handled by their contractors in a safe, secure manner. The contractors will be required to maintain safety, security and environmental monitoring programs as well as be responsible for other ordinary business contractual terms and conditions.

Resources:

Used nuclear fuel is made up of small diameter ceramic pellets contained in long metal-alloy rods bound into rectangular arrays called assemblies that were placed in the reactor to generate energy. To transport these used fuel assemblies, 24 – 61 assemblies are secured inside a metal-alloy “basket” crate sealed within a large canister with 1/2 – 5/8-inch-thick stainless steel walls protected by a robust NRC-certified heavy walled transport cask. The casks are specifically engineered to keep their sealed integrity during extreme circumstances, such as when subjected to hypothetical accident conditions such as a series of drops, sustained thousand-plus-degrees fully engulfing fire and when immersed for long durations under water.

Transportation

With the ISP CISF concept, we are effectively taking the canister from a concrete storage module at a reactor site and moving it to a concrete storage module at the WCS site.

During transportation, the transport cask surrounding the canister is specifically engineered with multiple barriers, including containment boundary, structural shell, gamma shielding material, and solid neutron shield. When the canister arrives at the ISP facility, it is sealed inside massive concrete storage modules with thick walls to ensure any dose is well within exposure regulations.

Since 1965, more than 2,700 shipments of used fuel have been safely transported nearly 2 million miles across the United States – and there has never been a radiological release caused by a transportation accident. To move the used fuel from a nuclear energy facility’s onsite storage to the CISF, the canisters are placed inside the NRC-certified transport cask for shipment by rail, heavy haul truck, or marine transport. Once the transport cask arrives at the CISF Transfer Building, the internal used fuel canister will be moved into a transfer cask on a specially designed truck-trailer for onsite delivery and placement in the interim storage module.

Globally, Orano transports more than 200 casks every year, with a total of nearly 10,000 used fuel casks safely delivered. During the company’s 50-plus years of experience transporting and storing used nuclear fuel around the globe by rail, truck, barge, and ship, it has gained unparalleled experience in ensuring that all infrastructure is appropriately robust and strengthened where needed to fulfill transportation regulations. Nothing moves on our U.S. infrastructure without evaluation, certification and attendant taxation by any and all concerned entities.

Resources:

- NUHOMS® MP197HB Transportation Cask

- Cask Destruction Tests (video)

- Safety Record of Transporting Nuclear Fuel

- NRC Transportation Backgrounder

Storage

We are regularly handling and transferring these canisters full of used nuclear fuel for utilities all over the country, and we have a personal interest in making sure we’re protected. Ensuring radiation containment is accomplished through advanced materials science, precision engineering, and layered protection, not just thickness. Beginning inside, the first layer of containment is the canister’s metal alloy egg-crate basket with fixed neutron absorbers and soluble boron to intentionally moderate the fuel’s radiation. The canister’s stainless steel wall is a significant second containment barrier with a carbon steel plug in the loading end sealed by two welded shut steel lids. Also, the used fuel canisters are always inside the additional barrier of another container, adding more layers of protection. The used fuel will never be removed from the original storage cask.

Since used nuclear fuel is a solid – not a liquid – it is also very unlikely to leak or come out of the numerous defense-in-depth barriers. To securely store the used fuel, the canisters are placed and sealed inside individual massive concrete modules. The above-ground, horizontal orientation of the NUHOMS storage module simplifies the used fuel canister placement, inspection access for the Aging Management Program (AMP), and eventual retrieval for transport to a permanent federal repository. The NUHOMS inspections tools can examine 100% of the canister surface for any microscopic degradation or concerns. If any concerns are identified, the fuel can be repackaged in another canister or the original canister can be sealed inside a larger canister and then placed back inside the module.

The 2014 NRC study determined that there is less than a one in a billion chance that radioactive materials would be released in an accident.

Resources: